What Is a Collider? How Ashtanga Practice Teaches Systems Thinking Through the Body

What Is a Collider?

In systems thinking, a collider is a variable that sits at the convergence point of two or more independent causal pathways. Unlike a mediator (which transmits influence from one variable to another) or a confounder (which influences multiple variables), a collider is influenced by multiple independent sources—and this seemingly simple distinction creates profound complications in how we understand cause and effect.

The mathematical structure looks deceptively simple:Variable X → Collider Z ← Variable Y

Two independent causes (X and Y) both flow into a common effect (Z). But here’s where it gets interesting: when we condition on the collider—when we only examine cases where Z occurred—we create an artificial correlation between X and Y that doesn’t exist in the broader system. The collider acts like a lens that distorts our view of causal relationships, making independent variables appear related simply because we’re observing them through the filter of their common effect.

Consider a classic example: talent and effort both contribute to professional success. Talent and effort are largely independent—some naturally gifted people work hard, some don’t; some less naturally gifted people compensate through tremendous effort, some don’t. But if we only study people who achieved extraordinary success (conditioning on the collider), we might observe a negative correlation between talent and effort. Why? Because within the successful group, those with less natural talent needed more effort to get there, while those with more natural talent needed less.

This observation, confined to successful people, might lead us to conclude that talent and effort are inversely related—when in reality, they’re independent. We’ve been fooled by the collider.

The Collider Paradox: Why Smart People Draw Wrong Conclusions

Collider bias is particularly insidious because it operates invisibly within populations we naturally study. We examine successful entrepreneurs, elite athletes, authorized teachers, published authors—all colliders that filter for certain outcomes. Our conclusions about what creates success are systematically distorted because we can’t see the much larger population that didn’t reach the collider condition.

This is why business advice from successful entrepreneurs is often contradictory (“Take big risks!” vs. “Be conservative and sustainable!”). Both groups exist within the success collider, but they represent different pathways: some succeeded because of risk-taking, others succeeded despite risk-aversion. The collider makes both appear valid when they’re actually describing independent variables whose relative importance we can’t assess by studying only successful outcomes.

Education research struggles with this constantly. When studying “effective teachers,” researchers condition on a collider (teaching effectiveness) that might be influenced by numerous independent factors: subject knowledge, pedagogical training, emotional intelligence, classroom management skills, cultural competency, administrative support, student population characteristics, and pure luck. Observing only effective teachers creates misleading correlations between these factors.

The medical field has learned this lesson through survivor bias—studying only patients who survived a treatment tells you very different things than studying all patients who received it. The survival collider filters the data in ways that can make harmful treatments appear beneficial if you’re not careful.

Colliders in the Body: The Ashtanga Laboratory

Here’s what makes Ashtanga practice remarkable from a systems thinking perspective: it’s a longitudinal, embodied experiment in collider recognition that happens largely beneath conscious awareness.

Consider a practitioner’s journey with a challenging posture—let’s use Marichyasana D (a deep twisting bind) as an example. Success in this pose is a collider influenced by multiple independent variables:

- Variable X₁: Hip external rotation range

- Variable X₂: Thoracic spine rotation capacity

- Variable X₃: Shoulder flexibility

- Variable X₄: Core stability

- Variable X₅: Breath control and nervous system regulation

- Variable X₆: Spatial awareness and proprioception

- Variable X₇: Prior injury history

- Variable X₈: Skeletal structure (femoral head angle, acetabular depth, etc.)

The pose itself—the ability to bind—is the collider. These variables are largely independent of each other. You can have excellent hip mobility but limited thoracic rotation. You can have strong core stability but restricted shoulder flexibility. The variables don’t cause each other; they each independently contribute to the outcome.

The First Collider Lesson: Your Struggle Is Not Their Struggle

In early practice, most students make a fundamental collider error: they assume their limitation is the limitation. If hip tightness prevents your bind, you might believe “this pose requires open hips.” But your practice partner who binds easily might have average hip mobility—their pathway to the collider came through exceptional thoracic rotation instead.

This is your first embodied encounter with collider bias. You’re conditioning on the outcome (successful bind) and observing someone who got there through a different causal pathway. If you conclude “I need to do what they did,” you’re likely working on the wrong variable for your system.

Ashtanga’s daily practice structure forces you to confront this repeatedly. You can’t skip ahead. You can’t avoid the poses that illuminate your particular constellation of limitations. Day after day, you meet the same colliders, and slowly—if you’re paying attention—you begin to recognize that different bodies navigate different pathways to the same outcome.

The Second Collider Lesson: Effort and Outcome Are Decoupled

A profound and often disturbing realization emerges in sustained practice: effort and progress don’t correlate linearly. Some poses that feel effortful for months suddenly become accessible. Other poses that seemed close remain stubbornly out of reach despite years of dedicated work.

This is collider dynamics playing out in real-time. Progress (the collider) is influenced by numerous factors: physical work, yes, but also rest, stress levels, hormonal cycles, injury recovery, aging, nutrition, sleep quality, life circumstances, and countless other variables you don’t control.

If you condition only on moments of progress (the collider), you might falsely attribute success to whatever you happened to be doing that week. “I finally bound because I started doing more hip openers!” Maybe. Or maybe your inflammatory markers finally dropped because you recovered from a cold. Or your nervous system regulation improved because your stressful project at work ended. Or your connective tissue adapted after months of consistent practice finally reached a threshold. Or all of the above.

The practice teaches humility about causation. You do your work, you show up consistently, but you learn to hold your theories about “what works” lightly because you’ve been fooled by colliders too many times.

The Third Collider Lesson: The Injury Crossroads

Injury introduces a particularly instructive collider: the moment where practice continuation becomes impossible. This collider is influenced by at least two independent pathways:

- Variable X: Accumulated tissue stress (overuse, repetitive strain, insufficient recovery)

- Variable Y: Acute incident (awkward movement, distraction, pushing too hard in one moment)

Many injuries sit at the intersection of both—chronic overload creates vulnerability, then an acute incident triggers the collapse. But here’s where collider bias becomes dangerous: if you only analyze the acute moment (“I got injured because I pushed too hard in that one practice”), you miss the chronic accumulation that created the conditions for injury.

Conversely, if you only focus on the chronic patterns (“I got injured because I’ve been practicing too intensely”), you miss the specific mechanical failure point that might be easily correctable.

The practice asks you to hold both causal pathways simultaneously—to recognize that the injury collider has multiple independent sources that require different interventions. This is sophisticated systems thinking, learned through painful necessity.

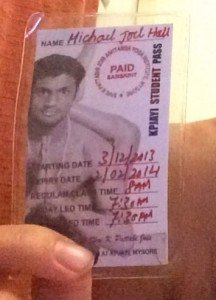

The Fourth Collider Lesson: Authorization and Its Discontents

For those who continue practice long enough to consider teaching, authorization becomes the ultimate collider—the convergence point of multiple independent variables:

- Practice depth (years of consistent practice)

- Asana achievement (ability to perform advanced poses)

- Financial capacity (ability to travel to Mysore repeatedly)

- Life circumstances (flexibility to take extended time away)

- Physical resilience (ability to practice intensively without injury)

- Cultural access (comfort navigating Indian social contexts)

- Relationship with authorized teachers (mentorship, visibility, approval)

- Age and timing (being at the right point in life when opportunities arise)

These variables are largely independent. Exceptional practice depth doesn’t guarantee financial capacity. Cultural access doesn’t cause physical resilience. Life circumstances don’t create asana achievement.

But because authorization conditions on all of these simultaneously (you need enough of most of them to receive authorization), practitioners who achieve it often misunderstand their own pathway. They might attribute their authorization primarily to practice dedication, not recognizing how financial privilege, injury-free genetics, or fortuitous timing contributed equally.

This is collider bias at the systemic level—and it’s why authorized teachers often struggle to understand why “just practice and all is coming” doesn’t work for everyone. They’re advising from within the authorization collider, unable to see the multiple independent variables that had to align for them to arrive there.

The Practice of Collider Recognition

What makes Ashtanga particularly powerful as a systems thinking laboratory is its temporal structure. You practice the same sequence repeatedly, creating longitudinal data about your own system. Over months and years, patterns emerge that reveal collider dynamics:

Pattern Recognition Through Repetition

When you practice the same pose hundreds of times under varying conditions—different times of day, different stress levels, different points in your menstrual cycle, different seasons, different years of your life—you begin to see how multiple independent variables influence the outcome.

Tuesday’s effortless bind and Thursday’s impossibly tight hips might have nothing to do with what you did in practice. Maybe it’s sleep. Maybe it’s inflammation from that meal. Maybe it’s cortisol from work stress. Maybe it’s weather-related joint fluid changes. The practice doesn’t let you ignore this variance; it makes you confront it daily.

This is empirical training in holding multiple causal hypotheses simultaneously—the essence of understanding colliders.

The Breath as Experimental Control

Ashtanga’s emphasis on ujjayi breath and breath-movement synchronization provides something rare: a relatively controlled variable you can observe across changing conditions. The breath becomes your instrument for detecting when other variables are active.

If your breath remains steady but the pose is harder today, you learn something about non-respiratory variables (tissue state, nervous system activation, biomechanical factors). If your breath becomes labored even though the pose feels physically accessible, you learn something about cardiovascular or respiratory variables. If both breath and physical sensation are affected, you’re observing a systemic state change.

This is experimental methodology, learned through embodied practice rather than abstract study.

Failure as Information

Perhaps most importantly, Ashtanga doesn’t let you avoid failure. You can’t curate your practice to include only poses you do well. The sequence is the sequence. Every practitioner has poses that remain challenging for years or forever.

This forced confrontation with limitation is actually forced confrontation with colliders. Every challenging pose is a collider you haven’t yet reached—an outcome influenced by multiple variables, at least one of which is currently insufficient in your system.

The practice asks: Can you work diligently on what you can control while accepting what you can’t? Can you recognize which variables are modifiable and which aren’t? Can you distinguish between “I need more effort” and “this pathway is blocked; I need a different approach”?

These are precisely the questions systems thinkers must ask when working with colliders. The mat becomes a laboratory for developing that discernment.

From Personal Practice to Teaching: The Collider Transfer

The tragedy and opportunity of Ashtanga teaching is that all of these embodied lessons about colliders should transfer directly to teaching—but often don’t.

A practitioner who learned through painful experience that their hip restriction required a completely different approach than their practice partner’s hip restriction might still teach as if everyone’s hips work the same way. They’ve learned collider thinking in their own body but haven’t generalized it to teaching.

Why? Because teaching authorization itself is a collider that filters for people who succeeded in the traditional approach. If the traditional approach worked for your body, you’re less likely to have developed the creative modification skills required to teach bodies unlike yours. The authorization collider creates a selection bias against the very teaching skills most needed for diverse students.

This is why the best physical therapists often aren’t former elite athletes—they developed their observational and problem-solving skills working with limited, injured, or unusual bodies. They learned to think in terms of multiple causal pathways (colliders) because they had to.

The Collider-Aware Teacher

What would teaching look like if practitioners transferred their embodied collider awareness to pedagogy?

Diagnostic Observation

Rather than prescribing universal modifications (“everyone should use a strap in this pose”), the collider-aware teacher observes which independent variables are limiting each student:

- Is it range of motion? (Which joint?)

- Is it strength? (Which muscle group?)

- Is it nervous system activation? (Fear, trauma, stress response?)

- Is it proprioception? (Spatial awareness, body mapping?)

- Is it skeletal structure? (Unchangeable architecture?)

- Is it breath pattern? (Accessory muscle dominance, paradoxical breathing?)

Each requires a different intervention. The pose (the collider) looks the same from outside, but the causal pathways are entirely different. The teacher who learned this in their own practice can see it in their students.

Pathway Flexibility

The collider-aware teacher doesn’t assume their pathway to a pose is the pathway. They can say, “I got there through hip opening, but I see your hips are mobile—your limitation is thoracic rotation. Let’s work with that.”

This requires epistemological humility: accepting that your embodied knowledge, while valuable, is pathway-specific. You learned one route to the collider. Your student might need an entirely different route.

False Correlation Recognition

Perhaps most importantly, the collider-aware teacher resists the temptation to make causal claims from their own success or their successful students. They don’t conclude “this approach works” based on observing people who succeeded—because those people represent the collider (success), which might have been reached through multiple independent pathways.

Instead, they track multiple variables across diverse students, looking for patterns that account for both success and failure. This is empirical thinking, not anecdotal thinking.

The Systems Practice

Here’s the profound realization: Ashtanga practice is systems thinking training. The daily repetition, the unchanging sequence, the confrontation with limitation, the variance across time, the decoupling of effort and outcome—all of this builds empirical reasoning about complex causal systems.

You learn in your body what data scientists learn in spreadsheets: that outcomes (colliders) are influenced by multiple independent variables, that correlation doesn’t imply causation, that selection bias distorts perception, that your particular pathway isn’t universal, that humility about causation is warranted.

The question is whether practitioners recognize what they’ve learned and whether they transfer it to teaching.

Most don’t, because the learning is implicit, embodied, largely unconscious. The practitioner who has sophisticated collider intuition in their own practice might still teach prescriptively, universally, without recognizing the systems thinking they’ve developed.

Making it explicit—naming the collider dynamics, recognizing the pattern, transferring the learning from personal practice to teaching methodology—is the work of conscious integration.

The Teaching That Could Be

Imagine a teacher training that began here: “You’ve been studying colliders in your body for years. Now let’s learn to see them in your students’ bodies. Now let’s recognize them in the authorization system. Now let’s identify them in the broader yoga world.”

The curriculum wouldn’t need to import systems thinking from business schools or policy analysis. It’s already present in the practice. It just needs to be made conscious and transferable.

- Module 1: Map the colliders in your own practice journey. What independent variables influenced your progress? How do you know? What evidence could disconfirm your theories?

- Module 2: Observe ten students in the same pose. Can you identify different limiting factors (different causal pathways to the same collider)? Can you design pathway-specific interventions?

- Module 3: Analyze the authorization system as a collider. What independent variables contribute to it? Which are necessary? Which are incidental? How does conditioning on authorization create selection bias?

- Module 4: Design teaching systems that account for multiple causal pathways. How do you assess which variables are limiting each student? How do you track which interventions affect which variables? How do you avoid false causation claims?

This would be teacher training that builds on what practitioners already know in their bodies, making implicit knowledge explicit and transferable.

The Practice Continues

The beauty of this approach is that it honors what Ashtanga already does well. The practice is teaching systems thinking through embodied experience. The daily repetition is creating longitudinal data. The confrontation with limitation is forcing recognition of multiple causal pathways.

We don’t need to abandon the tradition or import foreign frameworks wholesale. We need to recognize what the practice is already teaching and extend that learning to teaching methodology.

The collider recognition you developed through thousands of hours on the mat—that’s the foundation of sophisticated teaching. The question is only whether you make it conscious, whether you name it, whether you transfer it from your own practice to your observation of others.

The systems thinking is already there. The collider awareness is already embodied. The question is: Can we make it explicit? Can we teach it deliberately? Can we build authorization and teaching systems that reflect what the practice already knows?

That’s the work. Not importing systems thinking into yoga, but recognizing that sustained practice is systems thinking, and letting that recognition transform how we teach.

The collider teaches through the body what books teach through abstraction: that causation is complex, that your pathway isn’t universal, that outcomes emerge from multiple independent sources. The mat is the laboratory. The question is whether we transfer the lesson.